Chinese New Year is the most important holiday in Chinese culture. The most important meal of the year is the New Year’s Eve reunion dinner (年夜饭 / Nián yèfàn or 团年饭 / tuán niánfàn).

No matter where they live, all family members must return to their hometown. If they truly can’t, the rest of the family will leave their spot empty and place a spare set of utensils for them.

In the legend of the Spring Festival’s origin, this was when the monster Nian would come and terrorize the villages. The people would hide in their homes, prepare a feast with offerings to the ancestors and gods, and hope for the best.

As with Chinese New Year activities and decorations, the dishes are created to give blessings for the next year. Both the names and looks are symbols of wishes for prosperity, happiness and auspiciousness.

The same goes for the delicious desserts that come after the meal. While their names are more straightforward, each dessert is aesthetically and tastefully pleasing. Most are sweet, as it expresses the wish for a sweet year. Though every region (even household) have different customs, here are the most well-known and unique desserts.

Nian Gao 年糕 (nián gāo)

Nian gao, also known as “rice cake” or “New Year cake” in English, are a must for Chinese New Year. The “gao” in nian gao is a homophone of 高 (gāo—tall/high). It’s a wish to be successful and “higher” each year. Every year will be better than the last. Some funny parents like to tell their children that eating this will help them grow taller too.

They are either made of sticky glutinous rice or yellow rice, giving nian gao two major colors and textures. Depending on their shape, they can represent gold and silver bricks or bars. Nian gao was already popular during the Wei and Jin dynasties (220-420 A.D).

But after more than two thousand years of development, there is a crazy amount of variations. Nian gao from northern regions and the south almost seem like entirely different foods.

Southern nian gao are usually stir-fried with meat and vegetables for a savory dish. On the other hand, they appear as desserts elsewhere. Lard nian gao (猪油年糕 / zhū yóu nián gāo) from Suzhou are made from glutinous rice flour, sugar and lard.

In Beijing, jujube nian gao (红枣年糕 / hóng zǎo nián gāo) are popular. The cake is steamed in a flower mold and dotted in the center with a single jujube. On the other hand, people of Shanxi and Inner Mongolia like to deep fry the batter and add fillings of red bean paste and mashed jujube.

For the ones with a true sweet tooth, it’s also acceptable to directly dip nian gao in white sugar. The sweetness means the next year will be sweet and successful. (It’s a good excuse to gorge on candy!)

Fa Gao 发糕 (fā gāo)

As with nian gao, the “gao” is still a wish for success. In fact, almost all Chinese desserts with “gao” in the name have that meaning. What gives fa gao a unique meaning is the “fa.” It is the same as in 发财 (Fā cái), or gaining wealth and making a fortune.

Rice is soaked before ground into paste. The most important step comes next—fermentation. If the fermentation period is too short, the fa gao won’t be able to open up. So during this time, the paste must be stirred every few minutes.

Then it’s put in for steaming. The most nerve-wracking part of the making process is when the lid is lifted. Everyone holds their breath to check if the dough has raised well. The fluffier the cake is and the clearer the splits are, the better luck it will bring.

Corn flour can be used to create golden fa gao. Carrots results in a festive orange-red while green tea gives off a fresh spring feeling. Healthy red fruits such jujube, dates and hawthorn are often added too.

Turnip Cake 萝卜糕 (luó bo gāo)

Another cake, these are popular in southern China, especially the Fujian and Guangdong provinces. They also go by radish, carrot or daikon cake.

The main ingredient is shredded Chinese radish. In Chinese, “radish” (菜头 / cài tóu) has a similar pronunciation as “good luck and fortune” (好彩头). The shreds are added to rice flour and other flavoring ingredients.

In addition to shredded Chinese radish, you can also add bits of sausages, peanuts and other foods. Dried shrimp and shiitake are great to add to the mix as well. To add even more flavoring, the cakes can be dipped in sauces. Some suggestions are soy sauce, kumquat jam and hot chili sauce.

The pan-fried version has a thin crunchy shell, while the inside is still soft. The turnip cake can be customized to your tastes in the dimsum restaurants.

As a dish for the main course, Hong Kongers like to stir-fry the cake with XO sauce. In Taiwan, the turnip cake is a common breakfast dish. But in the Hakka ethnic culture, turnip cakes are a specialty on the 7th day of the Spring Festival.

According to legends, the world was created by the goddess Nu Wa (女娲). And on the 7th day, humans were created. For the Hakka people, turnip cakes are a must on this day because of its auspicious meaning. In Chinese culture, Chinese radish is also known as “the poor man’s ginseng.” Inexpensive but nutritious, they were much loved in ancient times. Nowadays, they are made to look like luxurious desserts and are a humbling reminder.

Hakka turnip cakes are generally less “fancy” than Cantonese or Taiwanese cakes. After steaming, diced green onions are sprinkled on and the cake can be brought to the table.

Osmanthus Jelly 桂花糕 (guì huā gāo)

The Chinese love adding flower petals to their desserts. Roses in the lard nian gao are only one example.

The sweet-scented osmanthus, or “may flower,” is often seen in Chinese celebrations. In Chinese, the flower’s name (桂 / Guì) is a homophone 贵, which means noble. In the Chinese flower language, it represents auspiciousness, friendship and success. It is a great ingredient for Spring Festival desserts.

Osthmanthus jelly has more than 300 years of history. True authentic jellies are made without any artificial flavoring or additives. The three main ingredients are glutinous rice powder, fresh osthmanthus petals and bits of crystal sugar.

Crystal osthmanthus jelly (水晶桂花糕 / Shuǐ jīng guì huā gāo) is a well-known Shanghainese dessert for the Spring Festival.

Jellies from Xianyang use a special osthmanthus jam. The petals are preserved for three years before adding in various Chinese herbs. The glutinous rice is stir-fried, ground, steamed and mixed with the jam. White sugar, black sesame and salt water are added to the dough. The end result is a dessert that is fragrant and soft, sweet and savory.

Jujube Flower Cakes 枣花糕 (zǎo huā gāo)

Jujube (枣—zǎo) is a homophone of “early” (早). They’re usually used a blessing to have children soon, or have wishes come true. People choose the meatiest jujube and wrap it with dough.

For the arrangement, some go for multi-tiered cakes. You can also mold the dough into a flower and simply press the fruit into the center or the petals. After steaming, the dough rises to a light spongey texture and you have a “bouquet” of jujube flowers.

Others use a more flaky pie-like type of dough to create small flowers. Jujube paste is used to fill the petals. The center of the flower is dotted with red food coloring.

No matter what you’re making, you can add some jujube for the extra taste and symbolic meaning.

For example, see the nian gao section.

In Fujian, jujube paste is also added to Chinese yam cakes (枣泥山药糕 / zǎo ní shān yào gāo). After steaming, the yams are soft enough to be mashed into dough. It is easy to mold and able to hold intricate designs. Sometimes, they’re too pretty to eat.

Ai Wo-Wo 艾窝窝 (ài wō wo)

The long and technical English term for this Beijing dessert is “steamed rice cakes with sweet stuffing.” This is another dessert that uses glutinous rice (as most Chinese desserts do), but traditionally, this is also halal.

In Beijing, ai wo-wo are sold from the Spring Festival all the way until the end of summer.

According to folktales, the one who brought ai wo-wo to Beijing was Concubine Xiang. She was of the Hui ethnicity and brought to Beijing for Emperor Qianlong (Qing dynasty). But she hated Beijing because it was far from home. And she had already been married!

So her previous husband made these treats from her homeland to help with her homesickness (and send secret messages.)

Ai wo-wo are known for their pure white color. Different from other desserts, the outside is not smooth. Glutinous rice is mixed into steamed rice powder to create the dough. The texture from the rice looks like freshly fallen snow and the inside fills you with sweetness.

Common ingredients for the filling include: sugar, black sesame, walnuts, bits of hawthorn and Chinese yam. Traditionally, jujubes are also pressed onto the top for more blessings.

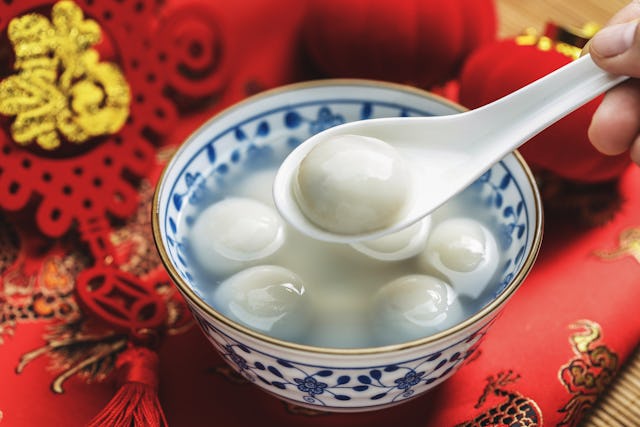

Rice Balls 汤圆 (tāng yuán)

Southern rice balls

In the south, these are known as 汤圆 (Tāng yuán), literally “soup balls.” It’s custom to eat them for the first breakfast of the year in Jiangsu and Shanghai regions. These glutinous rice balls are boiled and served in the hot water. Because it originated from Ningbo, they can also be called Ningbo rice balls (宁波汤圆 / níng bō tang yuán).

Most rice balls have sweet fillings, such as red bean paste, black sesame, mashed jujube, peanut paste and melted sugar. People have also tried adding cream, butter and chocolate. Occasionally, they can include vegetables or a meat ball.

For even more variations, the rice balls can be fried or steamed as well.

In Sichuan, a local tang yuan is 心肺汤圆 (xīn fèi tang yuán), literally “heart and lung rice balls.” The filling includes dried tofu and vegetables stir-fried with lard, and pot-stewed pig heart and lungs. For more taste, it can be served with green onions, diced garlic and peppers.

Northern rice balls

This dessert goes by 元宵 (yuán xiāo) in northern China. The difference between the two lies in the preparation process. Tang yuan are made like a dumpling. Sometimes a small point is added so it resembles a peach. In Chinese culture, peaches are a symbol of longevity.

On the other hand, yuan xiao start with the filling. The rice powder is then poured on and shaken until it forms a ball. They are eaten during the Lantern Festival (元宵节 / yuán xiāo jié), on the last day of Chinese New Year.

The Lantern festival lasted ten days in the Ming dynasty, but most activities only occur in one day now. Creating lanterns is the most important activity during the festival. Lantern Riddles (猜灯谜 / Cāi dēng mí) is a game played by writing riddles on lanterns. As it is a full moon that day, moon-gazing amidst lanterns is the best way to celebrate.

Just like the beginning of the Spring Festival, family reunion is the main focus of this festival. No matter what name it goes by, it includes a word pronounced “yuán” (圆/元). Yuan can mean circle and also sounds similar to “reunions” (团圆 / tuán yuán).

Other delicious desserts

The list of desserts that people bring in after the main course is endless. Here is a short list of some other traditional desserts:

- Taro balls (芋圆 / yù yuán): Steamed taro is mashed, rolled into balls and boiled. Like rice balls, they represent reunions and a successful career.

- Song muffin cakes (松糕 / sōng gāo): Traditionally, this is a wedding dessert. It can now be made for every occasion and represent sweetness in life.

- Yellow pea cakes (豌豆黄 / wān dòu huáng): This traditional Beijing dessert used to be a delicacy adorned with gold and served in the palace. It represents wealth and prosperity.

- Sesame balls (煎堆 / jiān duī): Sesame seeds are included into the glutinous rice dough. The balls are filled with red bean paste and deep fried until golden. They are crispy on the outside and warm and chewy on the inside. They are auspicious symbols of family reunions.

- Almond cookies (杏仁饼 / xìng rén bǐng): You should be able to find this traditional Cantonese dessert at your local Chinese food restaurant. They give them out as an alternative to fortune cookies (which, by the way, don’t exist in China!)

There is really nothing better than a good meal and dessert. There is no better feeling than the fullness after a good meal and dessert. It’s even better when the desserts are so intricately crafted and have such meaningful backgrounds.

The Spring Festival is a flurry of celebrations and activities. But between that are the meals. There is also time for you to munch on snacks. Together, the main dishes, desserts and snacks create a delicious menu for Chinese New Year.